For When They Try To MAke you take off your Kiffiye

or; Exploring the 2014 EU Human Rights Guidelines on Freedom of Expression

Ghassan Bardawil

01.12.23

We were walking down the right hand flank of the historic stock exchange, heading towards the front face of the building where the demonstration was taking place. Almost in a flash, six police officers on bicycles pulled up to us and swiftly formed barricades with their bikes forcing us into a tight space. “This scarf is not allowed, you should take it off” one officer said referring to my Kiffiye, “please put the flag away” they told my friend Céline. “We only want to make sure it doesn’t spark any violence, it’s for your protection”.

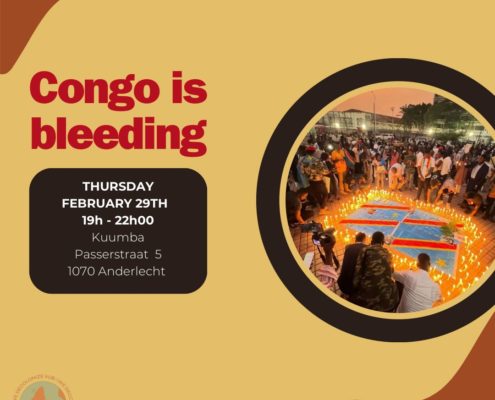

It was the 18th of October, and the nightly protest at Bourse was only on its second night. The day before, on the 17th, the occupation military had struck the Al-Ahli Baptist Hospital in Gaza massacring at least 470 patients, medical staff, and refugees taking shelter at the hospital, Thus kicking off the daily demonstrations in downtown Brussels. We had attended the protest the night before, and had also been harassed by the police for our scarves. These protests continue nightly until now, but have been moved to Central Station to make way for the christmas market (glaring irony).

The officers looked a little silly to me with their bicycle helmets, but the way they boxed us in was intimidating and the anxiety induced by the tight barriers made for a tense confrontation. “It’s only a piece of clothing, why are you so bothered that we’re asking you to take it off?”, one officer asserted. “If it’s only a piece of fabric then why are you so bothered that I’m wearing it?”. After a few minutes of stubborn arguing, I opted to put away my scarf. The protest was just around the corner anyway, and I knew I would pull it out as soon as I got there.

The moment passed relatively quickly but I was bitter about it for the rest of the night, so I spent my evening delving into EU law about rights for expression. I decided I would never let it happen again, and I knew that the police’s request was glaringly opposed to the advertised values and morals of the European Union. I will not allow them to rob me of my rights as an EU resident because I’m not white. I would not accept that my white friends could walk around comfortably with a Kiffiye without harassment while, when I wear it, it could ‘spark violence’ . Why are they granted the right to wear my culture around their neck when it’s ‘dangerous’ around mine?

I knew before starting I was putting together an arsenal of the master’s tools, Audre Lorde would not approve. And while I agree with professor Lorde’s assertion that we cannot dismantle the master’s house with them, I think they can be a vital defense when we are second-class residents of the same house. Portraying the stark contradiction between western liberal values and the restriction of this type of expression is a powerful way to highlight the double standards and institutionalized racism reflected in this type of behavior by the authorities. And when the next officer tries to approach me or you with a similar request, an assertion that our cultural representation and national identity are a threat to civil security, we will remind them of their own claimed values.

Among the sharpest tools in this shed is the 2014 EU Human Rights Guidelines on Freedom of Expression Online and Offline, which quite clearly lays out the EU’s contemporary definition of free expression. “States have an obligation to respect, protect and promote rights to freedom of opinion and speech” the guidelines lay out in the introduction. Part C of the document seeks to lay out definitions to the rights to freedom of opinion and freedom of expression.

“All forms of opinion are protected” Art. 13 asserts, “States may not impose any exceptions or restrictions to the freedom of opinion nor criminalize the holding of an opinion”. By this clause the state, or any authority representing the state, are revoked of any right to ask me to remove my kiffiye or to give me the impression that I cannot wear it publicly.

Art. 17 affirms that this protection extends to “ideas of all kinds that can be transmitted to others, in whatever form”. “Information or ideas that may be regarded as critical or controversial by the authorities … are also covered” the article asserts, providing examples “expression of ethnic, cultural, linguistic and religious identity and artistic expression … are also covered by the freedom of expression”. The clause denies the police officers any right to determine, by their own opinion, which cultural expression should or should not be considered dangerous.

Exceptions to the protected freedom can exist as outlined in Art. 19, “Freedom of expression can be limited by law in certain, strictly defined ways and under specific circumstances.”. However this also insists on the limits to restrictions themselves, “Restrictions on the exercise of freedom of expression may not put in jeopardy the right itself”. In turn Art. 20 presents a three-part cumulative test for restrictions, three principles are employed; the principle of legal certainty, predictability and transparency, the principle of legitimacy, and the principles of necessity and proportionality. It is within these principles we can find the root of the logic the police officers approached us with. Part 2 of Art. 20 implies that expressions which might threaten “public order” are subject to restriction. However, the same article provides the clincher, Art. 20 is presenting a cumulative test consisting of three parts, and so part 2 is not enough to constitute a cause for restriction if the expression does not also violate both parts 1 and 3. A restriction must also “be provided for by law” (part 1) and “proven necessary and as the least restrictive means” (part 3) to be deemed valid under the 2014 Guidelines.

The police had no right and no power in that moment on the street to decide that my kiffiye constituted a threat to public order or a violation of national security, article 17 explicitly strips them of this capacity. Even if they wanted to completely ignore Art. 17, Art. 20 further states that even if my kiffiye did constitute a threat to public order, their reasoning for asking me to remove it should have also been supported by a “law, which is clear and accessible to everyone”. Their request and reasoning seemed ludicrous to me now after having looked over the document. The articles I’ve highlighted here are only a few of many which reaffirm my rights to free expression.

You can find the 2014 EU Human Rights Guidelines on Freedom of Expression Online and Offline here and I hope that you can find a moment to look through it. Also, I encourage you to seek out more of the many EU and national documents and guidelines which our police officers and authorities seem to forget sometimes when they approach people of color. Additionally, check out Audre Lorde’s collection of essays The Master’s Tools will never Dismantle the Master’s House ; Professor Lorde is an amazing writer and, this collection in particular, presents many concepts which are critical for challenging institutionalized prejudice and oppression. As always, keep an eye on the blog and our social media for more content and upcoming events!